A Complete Guide to Chess Notation

One of the trickier aspects of transitioning to tournament play is getting used to writing down your moves (notation) as well as remembering to hit that @#%!& clock! As a chess player, you should be putting energy into figuring out the best play possible, not wasting brainpower on figuring how how to write down moves. Don’t worry, we have you covered.

Chess notation is a way of accurately recording and viewing chess games. Specifically there are two types of chess notation; the standard algebraic notation, and the antiquated descriptive notation. Famous games are recorded via chess notation and kept in perpetuity.

Chess notation is very valuable not only for appreciating games, but also as a means of instruction. I also love that I can actually replay chess games played in centuries past by famous people like Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, Karl Marx and others! Chess notation might seem intimidating, but don’t worry it’s not as bad as it seems. It’s also an essential skill if you want to transition to tournament play!

Algebraic Notation

Algebraic notation is the standard notation used in chess. It’s based on the fact that chess boards contain a system of coordinates. Each of the 64 squares on the chessboard have a unique name which is the letter of column, combined with the number of the row. So for example, the fifth row of column d is the square d5. When recording the square in algebraic notation, a lowercase letter is always used. When recording what piece was moved, uppercase letters are used!

The following are the abbreviations for the pieces (in English, they do vary by language). Some chess books, in order to be accommodating to audiences speaking a multitude of languages, will often times use figurines instead of letters to denote moves.

| Piece name | Algebraic Notation (English) | Figurine |

| Pawn | (No piece abbreviation) | ♙ ♟ |

| Knight | N | ♘ ♞ |

| Rook | R | ♖ ♜ |

| Bishop | B | ♗ ♝ |

| Queen | Q | ♕ ♛ |

| King | K | ♔ ♚ |

Keeping with the d5 example. If we have a Queen moving to d5, we would record that move on our scoresheet as “Qd5.” Remember, uppercase piece abbreviations, and lowercase square names.

Qd5

For pawn moves, there are no piece abbreviations, we simply declare the square name and it’s understood that what we recorded is a pawn move. A common way for white to begin the game is moving his pawn on e2 to e4. So the scoresheet would record the move number + the pawn move, and it would simply be “1. e4”

1.e4

In chess, a move is when both players have moved once. Therefore the “first” move of the game is white’s move and black’s reply. Using our example, if black replied with pawn to e5, you would write down “e5” beside the white move.

1. e4 e5

On white’s second move, he plays his knight to the square f3. Black responds with knight to f6. Therefore the second line of the scoresheet would look like this.

1. e4 e5

2. Nf3 Nf6

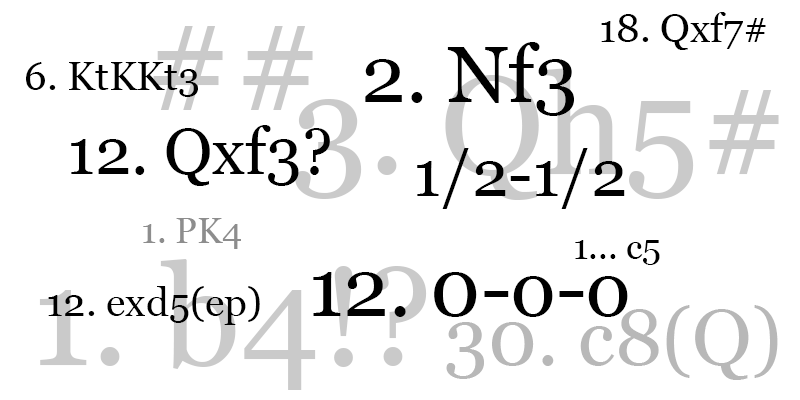

On the third move, white captures the pawn on e5. We have our first special case in the notation. Captures are notated with a lowercase x. Here is a list of special notation situations.

| Special Situation | Notation | Example |

| Capture | x | 3. Nxe5 |

| Castle kingside | O-O | 6. O-O |

| Castle queenside | O-O-O | 4. O-O-O |

| Check | + | 16. Qe2+ |

| Capturing en passant | e.p. | 11. exd5 e.p. |

| Pawn promotion | (Piece promoted to) | 31. e8(Q) |

| Checkmate | # | 14. Qxf7# |

The standard opening line for the Petroff has black reply with pawn to d6. White retreats his knight back to f3, then black recaptures on e4. Which would look like this.

1. e4 e5

2. Nf3 Nf6

3. Nxe5 d6

4. Nf3 Nxe4

Let’s play a few more moves and then we will talk about a few more special scenarios, but for the most part you’ve learned the bulk of algebraic notation! Our game will continue bishop to c4. The black will play knight to c6, and then white will castle. Remember, castling has a special notation. Castling on the kingside will be notated with “O-O” and castling on the queenside will be notated with “O-O-O.” For his sixth move, black will play bishop to g4.

1. e4 e5

2. Nf3 Nf6

3. Nxe5 d6

4. Nf3 Nxe4

5. Bc4 Nc6

6. O-O Bg4

The game will continue with white playing his knight to c3 for his 7th move, and black will get a little aggressive and play knight to e5?? Black is trying to ruin white’s pawn structure by forcing a capture on f3 and white will have to retake with the g-pawn exposing his king. This leads us to our next situation where sometimes you will see special marks after a move which have different meanings. This is a shorthand way of making notes on a scoresheet.

| Commentary Mark | Meaning |

| ! | Good move |

| !! | Amazing move |

| ? | Slight error |

| ?? | Crucial error (blunder) |

| ?! | Unsound or dangerous move |

| !? | Interesting move (may or may not be good) |

1. e4 e5

2. Nf3 Nf6

3. Nxe5 d6

4. Nf3 Nxe4

5. Bc4 Nc6

6. O-O Bg4

7. Nc3 Ne5??

The reason black’s 7th move receives a “??” indicating that it’s blunder is because he’s about to lose his bishop (or worse, get checkmated). This is a variation of a checkmate pattern called the “Legal’s Trap” (pronounced le-GAWL). White responds by ignoring the pin on his queen and playing Nxe5!! (amazing move!)

1. e4 e5

2. Nf3 Nf6

3. Nxe5 d6

4. Nf3 Nxe4

5. Bc4 Nc6

6. O-O Bg4

7. Nc3 Ne5??

8. Nxe5!!

It looks like black can gobble up that queen for free, but that’s another mistake. If black takes the queen, then white will checkmate with bishop takes f7 check (Bxf7+) followed by knight to d5 checkmate (Nd5#). Therefore, sometimes you will see parentheses in chess notation followed by some moves. This indicates an important variation from this moment.

Seeing this, black realized his best play is just to cut his losses here and play pawn takes knight on e5 (dxe5). This leads us to our next special rule about notation. Even though pawns do not have abbreviations like the other pieces, when a pawn makes a capture, it should be noted what letter column the pawn is on. In this case, black’s best move is for pawn (on d6) to take e5. Therefore the move would be written as “dxe5.” The reason this is done is sometimes more than one pawn can be simultaneously threatening a square. White will respond by taking the bishop on g4, and now he is up an entire piece!

1. e4 e5

2. Nf3 Nf6

3. Nxe5 d6

4. Nf3 Nxe4

5. Bc4 Nc6

6. O-O Bg4

7. Nc3 Ne5??

8. Nxe5!! dxe5

9. Qxg4

We are going to play a few more moves to illustrate a few more special situations and then you’ll be ready to record and replay games!

Blacks’ knight is in trouble so he’s going to retreat to f6 (trading knights would be a theoretical mistake!). White replies queen to e2. Black plays queen to e7. White plays pawn to d3. Now black writes “O-O-O” on his scoresheet. What did he just do? Before scrolling down and looking at the position below, see if you can remember what this special notation means.

1. e4 e5

2. Nf3 Nf6

3. Nxe5 d6

4. Nf3 Nxe4

5. Bc4 Nc6

6. O-O Bg4

7. Nc3 Ne5??

8. Nxe5!! dxe5

9. Qxg4 Nf6

10. Qe2 Qe7

11. d3 O-O-O

Black just castled on the queenside (or castled “long” in chess terms). We are almost done, but there’s one more important thing about notation you need to know! For white’s 12th move he will play pawn to a4, storming the black position. Black responds with pawn to g6, trying to free his bishop from its prison. White continues the pawn march with a5. Black plays bishop to g7 (a maneuver called a fianchetto). White gets his final piece off its starting square (and thus completing his opening goals) by playing bishop to e3.

Now black plays rook to e8 lining up a rook behind his queen. Ordinarily we would record this on his sheet as “Re8” right? Simple enough. But not so fast! Which rook did he move? Either rook we move to e8, the move would be recorded as “Re8” so that’s a problem. Just writing Re8 doesn’t give us quite enough information. This scenario pops up sometimes with rooks, knights, and pawns. So we simply add the column letter to the equation. If we move the rook on the h-file to e8, it would be recorded as “Rhe8” and the rook on d would be recorded as “Rde8.”

1. e4 e5

2. Nf3 Nf6

3. Nxe5 d6

4. Nf3 Nxe4

5. Bc4 Nc6

6. O-O Bg4

7. Nc3 Ne5??

8. Nxe5!! dxe5

9. Qxg4 Nf6

10. Qe2 Qe7

11. d3 O-O-O

12. a4 g6

13. a5 Bg7

14. Be3 Rhe8

Black’s having a rough day, let’s go ahead and put him out of his misery. 15. Bxa7! Pretty much everything black chooses here is a disaster, but let’s pick a move that will end him quickly …15. b6.

Sometimes you will see ellipses “…” followed by a number as in …15. b6. This usually is after some commentary about a white move and then the book will pick up indicating that …15. is black’s 15th move.

16. Bb5 Nd7?? And white has a win in hand. Can you find the winning move?

17. Ba6# 1-0

And finally, you will see 1-0, 0-1, and 1/2-1/2 at the end of a scoresheet. This indicates the outcome. In tournament play, when you win a game you receive a point. Drawing a game receives half a point. And losing is zero points gained or lost. So if white wins, she gets the point and black gets nothing. Hence “1-0.” If they tie, they each get half a point, hence “1/2-1/2.”

Now you can click through the full game taking everything you’ve learned! Pay attention to the parentheses, variations, comments, etc!

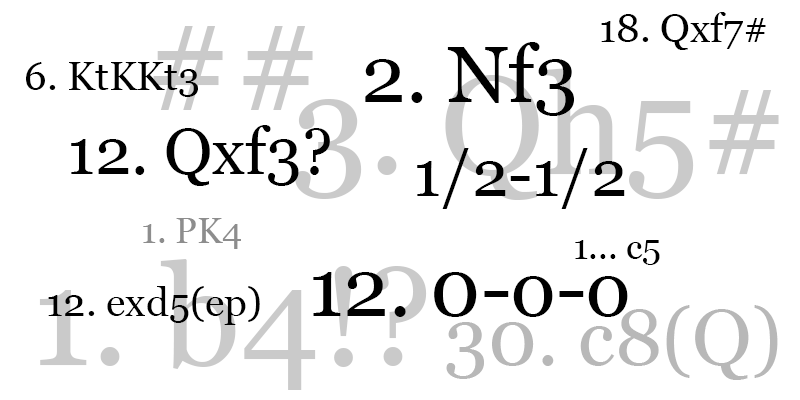

Descriptive Notation

Ok, we’re almost done. But first we need to give a shoutout to descriptive notation. It’s the “old” style of notation that is (mercifully) no longer used. Instead of using coordinates, it “described” the move via abbreviation. But gosh was it a mess. So in algebraic notation, moving the pawn in front of the king out two squares is called 1. e4. In descriptive notation it’s “PK4” which means “Pawn to the king’s 4th row.” Ok, not so bad so far. But if black responds with e5, his move is also recorded as PK4 because he’s moving his pawn to his king’s 4th rank. So it’s relative to the player, instead of absolute like a set of coordinates on a board.

Furthermore, knights were abbreviated Kt in this system which is easy to confuse with K at a glance. But it’s get’s better. That white knight who begins the game on g1? Yeah, he’s called the “King’s knight.” So he’s abbreviated “KKt” and the Bishop is “KB” and the rook is “KR.” So if you moved your knight to f3, what you’re doing in descriptive notation is moving it to your king’s bishop’s 3rd row. So in other words, “Nf3” in descriptive notation is “KtKB3” or “Knight to king’s bishop 3rd row.” So let’s compare our game in algebraic notation with descriptive notation side-by-side.

| Algebraic Notation | Descriptive Notation |

| 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nf6 3. Nxe5 d6 4. Nf3 Nxe4 5. Bc4 Nc6 6. O-O Bg4 7. Nc3 Ne5?? 8. Nxe5!! dxe5 9. Qxg4 Nf6 10. Qe2 Qe7 11. d3 O-O-O 12. a4 g6 13. a5 Bg7 14. Be3 Rhe8 15. Bxa7 b6 16. Bb5 Nd7 17. Ba6# 1-0 | 1. PK4 PK4 2. KtKB3 KtKB3 3. KtxP (Knight takes pawn) PQ3 4. KtKB3 KtxP 5. BQB4 KtQB3 6. O-O BKkt5 7. KtQB3 NK4?? 8. KtxKt!! (Knight takes knight) pxKt (pawn takes knight) 9. QxB KtKb3 10. QK2 QK2 11. PQ3 O-O-O 12. PQR4 PKKt3 13. PQR5 BKKt2 14. BK3 RKR1K1 (Rook on “King’s rook 1” to King 1) 15. BK3xp (Bishop on King’s 3 takes pawn) PQKt3 16. BQKt5 KtQ2 17. BQR6# 1-0 |

I hope you can clearly see what a confusing mess descriptive notation is and why it should never again see the light of day! However, it’s at least useful to be aware of because a lot of old, classic books use descriptive notation and there are still some great treasures to be mined out of them!