How to Improve at Chess: A Guide for Beginners

So how did a father of two, who only knew how to move the chess pieces, transform into a to a Class A tournament player and an amateur state champion? Spoiler alert; hard work. Chess improvement is both an art and a science which requires effort. But directing your effort into the right things, and avoiding the wrong things, will maximize your growth as a player!

Like anything else, improvement in chess comes with hard work, practice, and discipline. There are no shortcuts to getting good. But wasting energy on the wrong things will stall your improvement. Directing your energy on tactics puzzles, checkmate patterns, endgames, playing games, and reviewing your games will yield fantastic results.

Let’s discuss some more detail on each of these, and I will also provide a final bonus tip, what not to do that a lot of beginners do!

Tactics

There’s a popular quote by a chess master named Richard Teichmann that “chess is 99%” tactics.” While it’s possible Teichmann was embellishing a bit, it’s honestly not much of an embellishment. Tactics is defined as “a sequence of moves that limits an opponents options and may result in a tangible gain.” That’s a fancy way of saying “how the pieces interact.” If I move here, they will move here, etc. “If I can get her to move her queen onto this square, I can take it with my knight.”

Tactical ability is the cornerstone of becoming a great chess player. But what are tactics exactly? They are direct skirmishes between pieces. Who will come out ahead when our pieces fight? Contrast that with strategy, which is how you maneuver pieces when there are no direct threats to deal with. Put more succinctly, tactics is knowing what to do when there’s something to do. Strategy is knowing what to do when there’s nothing to do.

Let’s present an example. In this tactics puzzle, white is presenting a clear threat. White just moved his knight to b5 and is threatening to take the black’s dark-square bishop. White is also threatening to take the pawn on d4. Tactics is figuring out how to deal with these problems so white doesn’t come out ahead in this position. Black can’t really move the dark-square bishop off the diagonal it’s on, because it’s guarding the knight on h2.

A player with a strong tactical ability should realize that white has made a mistake in this position. White’s queen is overloaded. She is defending two pieces, the light-square bishop on e4 and the knight on b5. Black can come out ahead by taking the knight on b5, followed by taking the light-square bishop on e4 with his rook.

So how do you improve your tactics? Doing lots and lots of tactical puzzles! There are lots of great apps and sites to practice your tactical ability, but my favorite one is Chess Tempo. They’re a free site with tens of thousands of tactical puzzles and it allows you to track your progress and improvement over time. In addition, there’s a lot of users who discuss the tactical problem and explain why variants don’t work. If I can confer one piece of advice for chess improvement it’s this; do lots of tactical puzzles!

Checkmate Patterns

The object of the game is to checkmate your opponent. Therefore, knowing how to checkmate is a fundamental skill which is vital to chess improvement. Throughout the game, many checkmate patterns often present themselves.

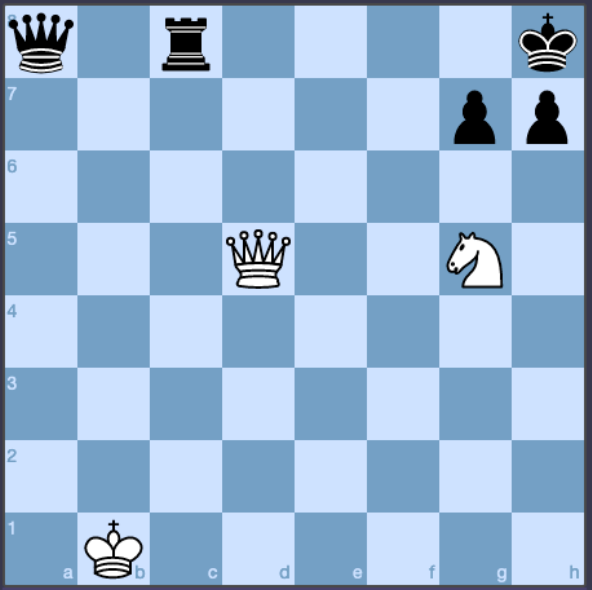

In the puzzle to the right, black is ahead in material big time. Four points, in fact. And if it were black to move, it would be game over. However, it’s white to move and it’s actually black that’s toast. White has black trapped in a checkmate pattern called the Smothered mate. It’s a forced checkmate in 4 moves. Can you figure it out?

So how do you learn checkmate patterns? By far my favorite resource on this is a popular book called Chess: 5334 Problems, Combinations, and Games by Lazlo Polgar (father of the world famous Polgar sisters). Some coaches recommend that new students do the 306 “Checkmate in One” puzzles in this book every day until they reach master.

Endgames

There’s another popular saying in chess, “when you study openings, you study openings. But when you study endgames, you study chess.” I absolutely love this quote, and I believe it has a lot of value. Russian coaches begin young players with endgame study. They don’t even set up all the pieces on the board. Russian coaches teach young students the game of chess with how to checkmate a king with just a king and another pawn on the board. Beginning with the end in mind.

The wisdom is sound. As the game goes on, the player with the superior endgame knowledge grows stronger and more confident. The endgame is also what separates good players from world-class players. The best thing about endgames is they are finite and objective. They’re solved. There is no new “endgame theory” that will emerge in the years to come. Chess endgames techniques such as the Philidor position, are as certain as 2+2.

So how do we learn these endgames? Three absolutely fantastic resources on this subject is International Master Jeremy Silman’s “Silman’s Complete Endgame Course“, Grandmaster Jesus de la Villa’s “100 Endgames you must know,” and Irving Chernev’s “Capablanca’s Best Chess Endings: 60 complete games.“

The first two recommendations teach you the techniques, and they are unparalleled. The last book teaches you the style, art, and mindset of playing endgames by giving you annotated games of, arguably, the greatest chess player to ever live, Jose Capablanca. You cannot go wrong with these books.

Play Chess

Play lots and lots of games! A lot of chess is pattern recognition, and one of the best ways to galvanize patterns in your mind is by playing lots of games. In-person games are best, but you can play lots of games online for free in a very short amount of time. Two great resources for playing games are Chess.com and Lichess.org.

Review Your Games

Once you begin playing in-person games, do take the time to review your games with a stronger player. It’s common courtesy in tournaments to offer your opponent to review the game when it’s concluded. Never skip this opportunity, especially if you lose! You will never learn more about the game of chess than when you lose a game. It’s not hard to run your game through a computer and it will tell you what a good or bad move is, but computers are not great at explaining why something is a bad move. Humans are.

Chess clubs around the world are often filled with enthusiastic players who are willing to take the time to instruct and guide new players. Find a local club and you’re sure to meet some very good (and very interesting) people!

What You Should Not Do

For some reason, almost every new player makes this same mistake. Do not waste your time studying openings. When you’re first beginning, learn the opening principles. Spend the majority of your time on tactics! A lot of beginners will get snared by studying openings, and try to memorize a bunch of trap or gimmick openings. Do not do this. It’s a waste of time and energy. Sure, it’s fun to go for a quick win or a flashy victory, but it’s not good for your development as a player. In fact, it’s detrimental!

A few years ago, the makers of the popular chess software “Fritz” set up an experiment by creating two computer opponents. Computer player A had a complete knowledge of openings as well as every endgame database, but it’s playing strength was set to 99 out of 100. Computer player B had no opening books to draw from, and no endgame databases. But it was set to a playing strength of 100. With only a 1% difference in tactical ability, and Computer player B dominated a 30-game match!

Study tactics, not openings.